Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts

Friday | May 6, 2016 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

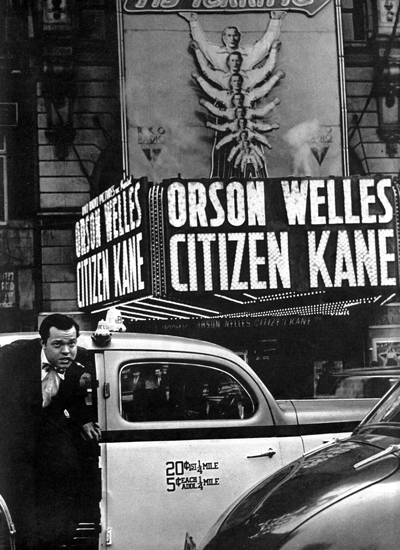

Kristin and I are one-third through our New York stay, and blogging has suffered. There have been talks to give, old friends to visit, new friends to meet, and movies and exhibitions to see. And there’ll be more activities of these sorts to come. But I can’t let 6 May pass without some acknowledgment of Orson Welles.

That’s partly because I just finished a draft of the Welles section of my 40s Hollywood manuscript. (Yeah, that beast was another distraction from blogging. All 158,000 rough-hewn words of it are now dispatched to some unwary readers.) So Welles was on my mind already when the anniversary of the “official” Citizen Kane release came up on 1 May.

Actually, by the time Kane had that roadshow release, it had been widely seen by the Hollywood community. In the face of the Hearst press’s attacks, RKO head George Schaefer held invitational screenings in early 1941 to build up support for the film. Variety estimated that by late March 1,200 producers, directors, writers, actors, and agents had seen the picture. The number was so big that RKO dispensed with a splashy Hollywood opening. (The article title is pure Varietyese: “So Many Cuffo Gloms at ‘Kane’ It Kayoes Idea of a $5.50 Preem,” Variety, 2 April 1941, 2, 20.) As a result, I think, Kane‘s influence began to be registered some months before its New York premiere, as the look of The Maltese Falcon (shot June and July of 1941) might suggest.

What I offer today, on the Boy Wonder’s birthday, is a consideration of that movie from an unusual angle looking not just at its originality but also at its shrewd consolidation of a variety of techniques.

Wellesapoppin’

We’re so used to considering Kane powerfully original that it’s worth remembering that it synthesizes a lot of traditions. I’m not thinking of Pauline Kael’s claim that it’s a culmination of the 1930s newspaper genre; as so often, she fails to persuade me. I’m thinking instead of the look and sound of the movie, as well as its storytelling strategies.

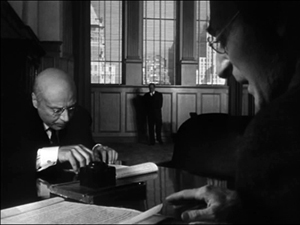

Depth staging and deep-focus cinematography are two techniques not always kept distinct in critical discussion. 1930s Jean Renoir films have plenty of depth staging but usually not so much deep focus. Citizen Kane won attention partly because it has plenty of both, and in exaggerated form. The figures often stretch very far back, someone or something is often rather close to the camera, and often all of them are sharply focused.

Without taking anything away from the boldness of Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland, we should recognize that they reworked visual patterns—what I’ll call schemas—that were already circulating in filmmaking. Framings with big foregrounds, distant planes, and low angles weren’t unknown in silent films (Opium, 1919; Greed, 1925; A Woman of Affairs, 1928) and some early talkies (No Other Woman, 1933).

There was a sort of fad for such deep staging, especially with wide-angle lenses, during the late 1930s, though all the planes weren’t usually kept in focus. Some directors, such as John Ford (here and here) and William Wyler, favored deep images, while art director William Cameron Menzies (see here and here) made them part of his artistic signature. Below: Ford’s Long Voyage Home (1940), shot by Toland, and Menzies’ Our Town (1940), directed by Sam Wood.

It’s now acknowledged that many of Kane’s deepest shots weren’t actually made in the camera, but by means of special effects, particularly matte shots. Interestingly, this too wasn’t utterly original; compare the composite shot from Kane with the one from Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935), which has an even more aggressive foreground.

Welles and Toland called attention to these techniques by a radical gesture: many of these deep shots are long takes from a fixed camera position. Most filmmakers who used these depth schemas inserted them into passages of orthodox scene dissection. The depth shots might establish a locale, or they might be inserted into a series of analytical cuts, or they might be part of a shot/ reverse shot pattern. But in Kane you’re forced to notice the Baroque plunge of space because the lengthy take rubs your nose in the flashy composition.

It’s clear that Kane crystallized a certain look that was picked up by John Huston, Anthony Mann with or without his DP John Alton, and many other directors. The Welles/Toland version of depth consolidated a visual style that dominated American black-and-white filmmaking into the 1960s. Typically, though, filmmakers didn’t rely on the fixed long take as much as Welles did in Kane. Even Welles gave up that option in favor of dynamic editing of deep-focus shots, as in The Lady from Shanghai (1948) and Othello (1952/1955).

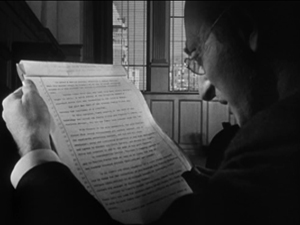

Not everything is long takes and depth. The pictorial variety of the film is, I think, unprecedented. The “News on the March” sequence becomes a virtuoso exercise in all the techniques that the rest of the film won’t be using. For perhaps the first time in history, Welles artificially distresses his staged scenes to make them match archival footage. He adds scratches and light flares.

This newsreel is so film-savvy that it can build in jump cuts and fast-motion as guarantors of fake authenticity. One passage mimics two-camera reportage, allowing us to imagine paparazzi crouched and perched at a fence to grab clandestine shots of an elderly Kane.

Here the schemas that are borrowed come from archival and documentary traditions, repurposed to add realism to this fictional biography. Welles, as we’ve seen in the Great Ambersons Poster Mystery (here and here and here), was a smart-alec cinephile: your disobedient servant.

What about sound? Back in 1994, Rick Altman wrote a pioneering article showing how Kane manipulates our sense of auditory space, and he connected that to Welles’ use of radio conventions. Contrary to what we might expect, Welles’s soundtrack doesn’t create much “deep-focus sound”; Altman shows that our impression of that is created chiefly by an overall reverberation rather than precise placement of sonic events. Altman also stresses Welles’ use of sudden, loud sound events to start or end a scene–another radio technique.

Today we’re lucky to have a great many of Welles’ radio programs available on the Web, and we can appreciate how his rich soundscapes mingle noises, dialogue, and voice-over narration. These shows remain very gripping. Listening to Kane in the same spirit, I’ve been impressed with how talky it is, how sounds crash in on you, and how even bursts of silence can be startling. Welles told one biographer that he aimed to create spiky transitions, both visual and sonic, because he thought most films of the period were dull.

He had already made his stage reputation on “shock effects,” those stunning high points in particular productions: the death of Macbeth in the Harlem production (1936), an actor’s headfirst tumble into the orchestra pit in Horse Eats Hat (1936), the mob’s murder of Cinna the Poet in Caesar (1937), the guillotine scenes in Danton’s Death (1938), and police agents firing from the audience in Native Son (1941). He became known as a director of thrilling moments, ever willing to sacrifice steady buildup to anything that would astonish. Forties theatre critics had a name for it: “Wellesapoppin’.” That quality dominates Kane’s images and sounds.

Remembering, recounting, replays

Otto Hullet, Barbara O’Neill, and Orson Welles in Sidney Kingsley’s Ten Million Ghosts (1936).

Just as Kane amplifies visual and auditory schemas already in circulation, the film does somewhat the same thing to narrative strategies. The key innovation here involves flashbacks and point of view.

Flashbacks were rare in the 1930s, but the early 1940s began a flashback craze that continued throughout the decade. Between August 1940 and December 1941, every top studio tried out flashbacks in a major release: The Great McGinty (Paramount), Kitty Foyle (RKO), I Wake Up Screaming (Fox), H. M. Pulham, Esq. (MGM), and Strawberry Blonde (Warners). A reviewer claimed that the “retrospective viewpoint” technique in A Woman’s Face, released the same month as Kane, “had of late become commonplace.” By September 1941 the Los Angeles Times critic considered the technique overused.

Even though the trend was already launched, Kane probably strengthened Hollywood’s inclination toward time-shifting. Again, it crystallizes in an influential way possibilities opened up in film, radio, theatre, and other media.

Kane’s central premise—a dead man recalled by one or more survivors—had been rehearsed in earlier films. The Power and the Glory (1933), scripted by Preston Sturges, was probably the most noted experiment in that vein. (For more, see this long-ago entry.) Another example was The Life of Vergie Winters (1934), which begins with a funeral procession and flashes back to the start of a backstreet love affair. (See this entry.) The Escape (1939) centers on a doctor who tells a crime reporter about a recently deceased neighborhood gangster, and flashbacks enact his tale.

These earlier examples stick to a single teller, while Kane offers reports on its dead man from five characters. Here again, however, there are precedents. In fiction and drama, trials have long served as motivation for flashbacks from multiple viewpoints. A major example, perhaps the first, is Robert Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). Multiple tellers recounting events in flashback were staples of Hollywood courtroom dramas too. Beyond the trial-based format, Welles’ radio programs had welcomed multiple storytellers, sometimes embedding them within one another’s tales, sometimes letting them banter with each other.

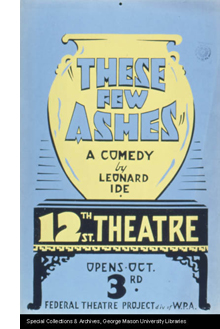

Kane assembles views on a person rather than evidence of a crime, but even this is not completely unknown. Some playwrights had tried out what Kane screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz had called the “prismatic” approach to an absent central character. Sophie Treadwell’s play Eye of the Beholder (1919) portrays an offstage woman as seen through the eyes of her former husband, her lover, her lover’s mother, and her own mother. The play These Few Ashes (1928) presents the life of a (supposedly) dead roué through the recollections of three women, each of whom sees him quite differently.

Then there’s reporter Thompson’s investigation. The Power and the Glory’s exhumation of the tycoon’s past is presented simply as his old friend’s recounting; it’s not the investigation of a mystery. Kane innovated in the biographical film genre by creating curiosity based on the dying man’s last word, “Rosebud.” That device shifts us to the terrain of the detective story. The dying message had become a mystery-tale convention from Conan Doyle onward, and Welles and Mankiewicz shrewdly recruited it for their purposes (although it’s not clear exactly who hears Kane say the crucial word).

In blending conventions of several genres, Kane motivates the flashbacks on diverse grounds. The film’s detective-story side is anticipated by The Phantom of Crestwood and Affairs of a Gentleman (1934); in both, flashbacks represent the suspects’ answers under questioning. Like The Escape, Kane uses a reporter’s search for a story to justify its flashbacks, and the reporter isn’t the protagonist (as he’d be in a typical newsman movie). And being something of a biopic, Welles’s film can trace the rise of a great man from the vantage point of old age, as in Edison, the Man (1940). By the way, that’s another film of the era using a journalist’s questioning to launch flashbacks to a person’s life.

Another wrinkle: Kane’s flashback organization skips around in the past. Episodes of Kane’s life are not presented in 1-2-3 order. Plays set in courtrooms, such as Elmer Rice’s On Trial (1914), had rendered flashbacks out of sequential order, and so had radio dramas. Welles’ 1938 radio adaptation of Dracula shuffles episodes in the manner of the source novel. Non-chronological strings of flashbacks weren’t common in film, but The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932) and The Power and the Glory used them significantly.

Even rarer is the replayed flashback, the scene from earlier in the film that is repeated, usually to reveal something we hadn’t caught on the first pass. Kane has occasion to present a brief replay from differing character viewpoints. Susan’s opera premiere is first treated curtly, as the object of the stagehands’ scorn. Later, in her flashback, the same scene registers the central characters’ reactions: a severe Kane, a bored Leland, the harried singing master, and above all the panicked Susan.

Replay flashbacks were rare in the 1930s, but The Witness Chair (1936) provides one example. After Kane, they would become more common, with Mildred Pierce (1945) offering one of the period’s most complex examples. (I discuss it here and here, with a video here.)

Even the coup de théâtre of following Kane’s death with a newsreel can be seen as revising a schema. “News on the March” isn’t exactly a flashback, but it provides exposition by shuttling among time periods in a manner characteristic of the film to come. Projected headlines and documentary footage, faked or actual, had found their way into 1930s theatre practice, notably in the WPA Living Newspaper productions. Many 1930s films opened with montage sequences using headlines, stock footage, and voice-overs like those in newsreels; The Roaring Twenties (1939) is a bold example. Gabriel over the White House (1933), with its mix of library footage and staged shots, anticipates Kane somewhat, as does Welles’ script for an uncompleted 1939 RKO project, The Smiler with a Knife, which includes a newsreel surveying the career of the fascist villain.

Another, less proximate source may be Sidney Kingsley’s 1936 Broadway play Ten Million Ghosts. This strident antiwar tract lasted only eleven performances and was never published; I took a look at a copy of the script last week. In the original production Welles played the naïve young poet André in love with the daughter of a munitions magnate during World War I.

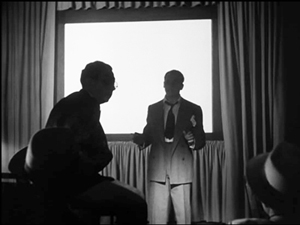

Ten Million Ghosts includes a scene in which arms makers spend an evening watching a battlefront newsreel in their parlor. Kingsley’s purpose is to show the capitalists as utterly indifferent to the slaughter that the camera records.

They watch in silence for a while. Then there are technical comments on the explosives, shells, etc. as we see them hurl geysers of earth and men into the sky.

Was this embedded newsreel an early source for News on the March? Scholars have wondered. And there’s more.

As the film unwinds, André, who has learned that his family has been killed in the war, cries out in protest. Madeleine is torn between him and her father. To win her over her father angrily defends his double-dealing between both sides in the war. It’s all just business, he insists. Then we get this piece of action:

De Kruif rises, intercepting the beam of the projecting machine, his face highly lighted, his shadow, black and ominously magnified, thrown on the screen superimposed over the pictures of men writhing in bloody destruction.

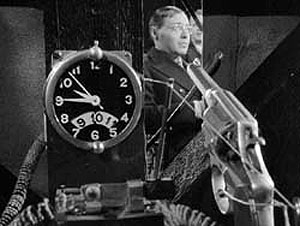

Was De Kruif’s moment in the play a visual idea that inspired Kane’s projection-room scene? If so, Welles and Toland revised the premise of the play. Instead of the rather obvious looming shadow cast on the screen, the story editor is a silhouette against the blank white rectangle, and then, in a reversed setup, he becomes another silhouette, this time splitting the projector beam.

Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that he never saw the projection scene in Kingsley’s play because he was always back in his dressing room at that point. But as Pat McGilligan points out in his new biography Young Orson, Welles could hardly have been unaware of the film-within-the-play; many critics commented on it. More decisively, in the playscript, André is clearly onstage during the screening. He cries out against the carnage: “Look, look! Those are only pictures. . . Out there it’s real. . .” Peter Noble’s 1956 biography The Fabulous Orson Welles quotes Welles as declaring that this scene left a strong impression on him.

It’s not enough just to mention some sources. If you practice historically-slanted criticism, you need to ask not only “Where from?” but “What for?” In other words, you have to ask how elements that a filmmaker inherits get repurposed for the particular movie.

So, for instance, Kane’s depth-designed images held in long takes allow a more “theatrical” shift of attention within a visual field (driven largely by following who’s speaking). They also create contrasts of scale and visual weight. And each scene will have its specific demands that the depth technique fulfills. A depth shot can present cause and effect in the same frame, and it can build suspense by letting us await Kane’s interference in a foreground situation.

Similarly, Kane’s narrative strategies, synthesizing so many earlier efforts, blend to create a mystery that isn’t about whodunit but rather “why’d he do it?”

I’m not exactly saying that everything is a mashup. But that slogan does capture the fact that in art nothing comes from nothing. Kane blends several options that had been circulating in popular culture and high culture for some years. Like others before and since, Welles revised schemas tried out earlier; he combined some, exaggerated some, and infused many of them with new force. Because of his film’s prestige, he gave thrusting imagery, bold sonic manipulations, and complicated time shifts a new prominence in Hollywood filmmaking. The Forties had begun.

There are a several essential Welles sources. Apart from the many fine critical studies (see especially Jim Naremore’s Magic World of Orson Welles and Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?), the biographical surveys I habitually turn to are Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This Is Orson Welles (Da Capo rev. ed., 1998), with a painstaking chronology by Jonathan Rosenbaum; the three-volume Simon Callow biography; Bret Wood’s Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood, 1990); Barbara Leaming’s Orson Welles: A Biography (Viking, 1985; my reference to shock effects is from p. 338); Frank Brady’s Citizen Welles (Scribners, 1990); and most recently Pat McGilligan, Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane (Harper, 2015). Pat’s discussion of Ten Million Ghosts is on pp. 366-367; Welles’ misremembering of the production is on p. 78 of This Is Orson Welles. A typescript of Kingsley’s play is held in the New York Public Library, at the Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts.

Rick Altman’s study is “Deep-Focus Sound: Citizen Kane and the Radio Aesthetic,” Quarterly Review of Film & Video 15, 3 (1994): 1-33. If it’s available without cost online, I haven’t found it. The programs “Dracula” (1938), “The Hurricane” (1939), and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” (1940) provide vivid examples of multiple narrators and embedded flashbacks. For a comprehensive account of Welles’ radio work, see Paul Heyer, The Medium and the Magician: Orson Welles, the Radio Years 1935-1952 (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005). As for prismatic flashbacks, in the mid-1930s, Mankiewicz had built the plot of an unfinished play around the memories of people who had known John Dillinger. See Richard Meryman, Mank: The Wit, World, and Life of Herman Mankiewicz (New York: Morrow, 1978), 247, 258.

On Kane‘s visual style and its place in film history, see my accounts in The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985) and On the History of Film Style (1997), as well as on this site (here and here especially). A detailed analysis of Kane‘s narrative strategies is in Chapter Three of Film Art: An Introduction, 11 ed., (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2016). The distinction between depth staging and deep cinematography is explored in Chapters Four and Five.